Untranslatable

BY: LAMAR KASSAB

IMAGES BY WINTA ASSEFA

The room buzzed with the sound of pencils scratching paper, chairs scraping against the floor, and whispers of conversations I couldn't understand. I sat stiffly at my desk, my hands fisted so tightly my knuckles turned white. The word foreign hung over me like a storm cloud, relentless and unshakable.

I was foreign. Foreign to this country, foreign to this language, foreign to the people around me. I glanced at the fluorescent lights overhead, their glow washing over the classroom. The teacher, Mr. Brown, was scribbling on the whiteboard. I tried focusing on his writing, but words merely swam in front of my eyes, incomprehensible and overwhelming. It felt like staring at a locked door without a key. He turned back and smiled at me–a gesture of reassurance–but I couldn't meet his eyes. My English was limited to the basic phrases my father had hammered into my brain that morning: I understand, and I don't understand. But today, I didn't understand anything.

Mr. Brown crouched beside me. “Would you like me to move your desk next to someone else?” he asked kindly, but his words made me flinch. I stared at him, eyebrows furrowing in frustration as I tried and failed to decode his words. He pointed to my desk and another, bringing his fingers together. Realization dawned, and I sank back into my seat, shaking my head reluctantly. He nodded, pulled out a phone, and placed it on my desk.

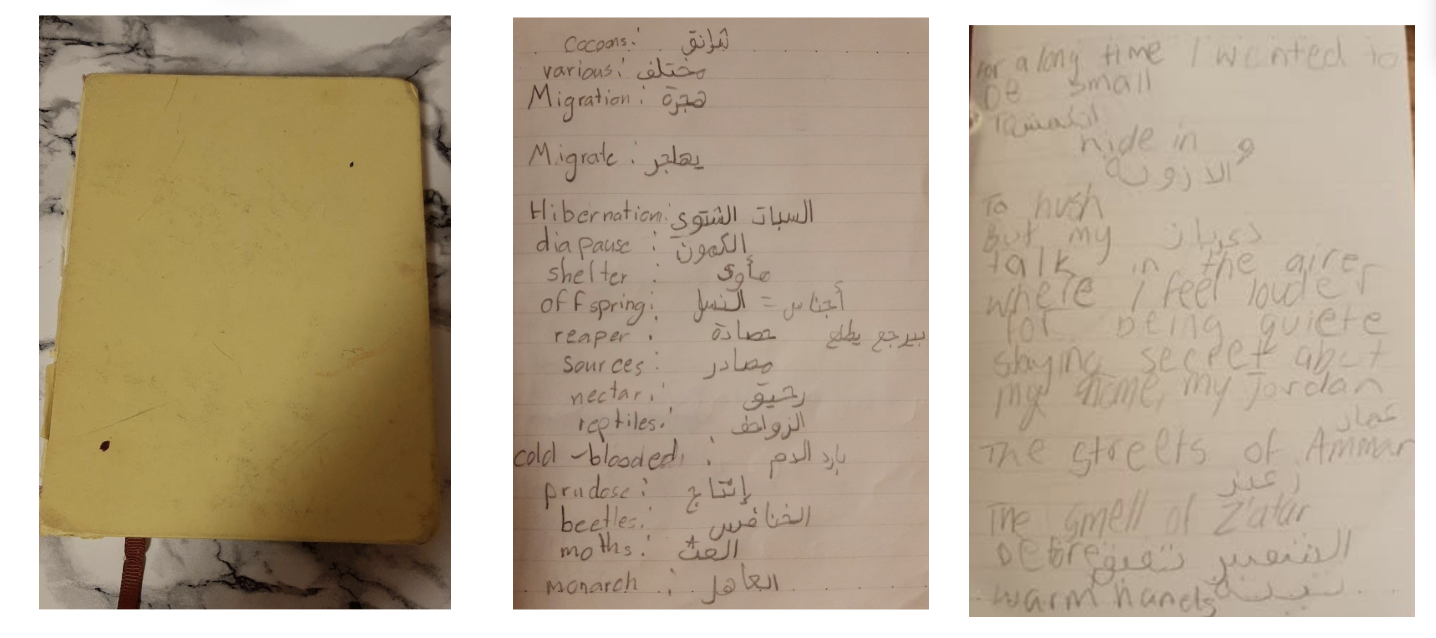

I glanced between the small, blue phone and his encouraging eyes. It was open to Google Translate, showing Arabic words: "It's okay if you're not ready to sit with someone else yet. In the meantime, you can use my phone anytime for Google Translate. We can make a dictionary together." He handed me a tiny yellow notebook, leather-bound with a diamond design. I ran my hands over it, flipping through its empty pages—empty, like how I felt.

Around me, kids chattered and laughed. Their words were like a river, flowing past me too quickly to grasp. I imagined myself drowning in it, lungs filling with confusion, my voice slipping beneath the current.

~ ~ ~

Three months earlier, I stood under the sweltering Jordanian sun, the scent of spices from the market below clinging to my clothes. Jordan had been our home for four years since we fled Syria when I was three.

We lived in my grandma Teta’s tiny upstairs apartment—my mother, sister, brother, and me—while my father was in Canada securing a visa for my mom. We barely scraped by, paying daily fees to stay in Jordan, clinging to false hopes of leaving.

So when my mom walked in, her usual smile resting on her face despite all the stress and hardship she'd been enduring, "We're going to Canada," she announced. I only nodded, not believing anymore.

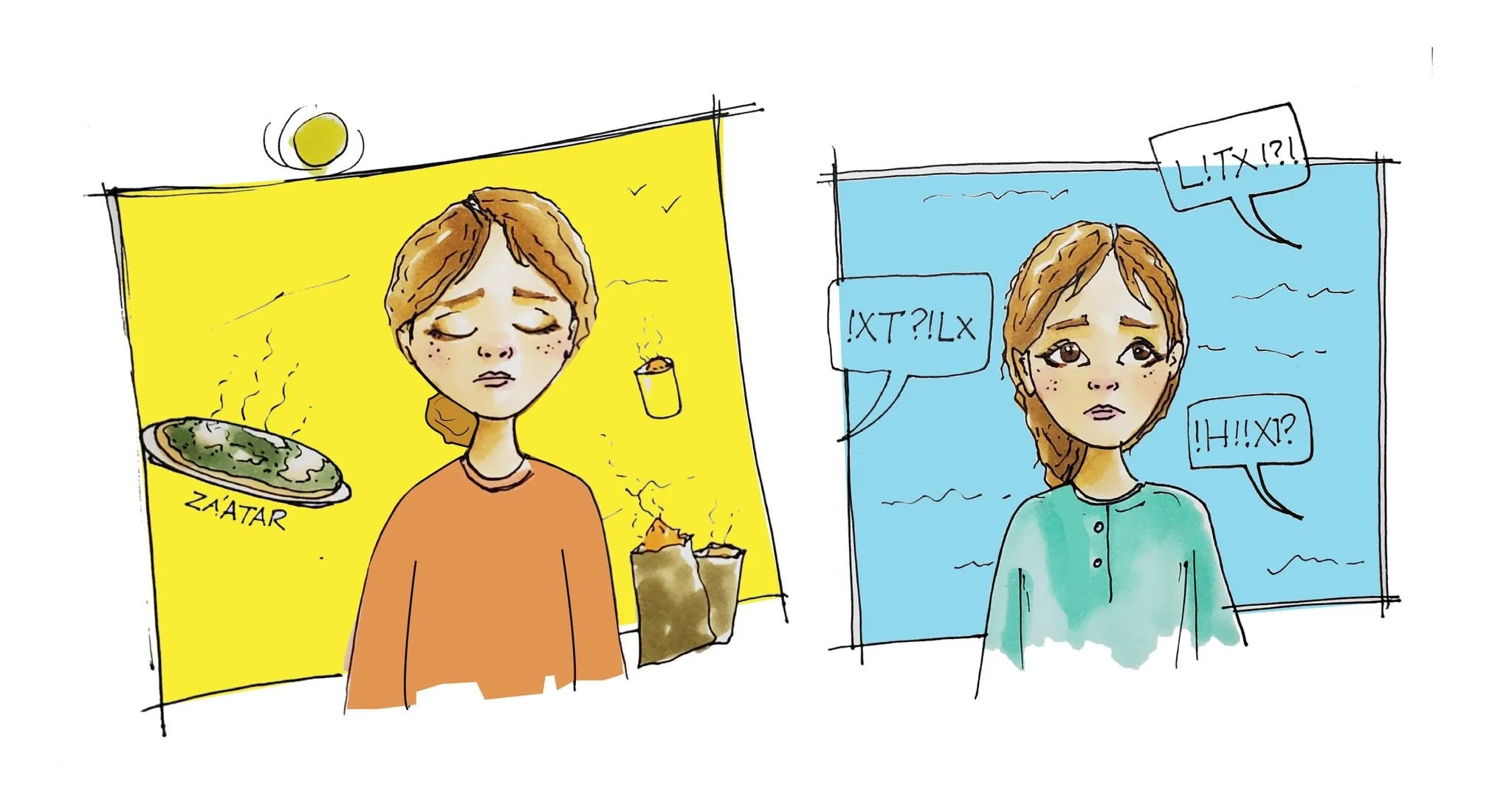

It was only when I packed my bag and hugged my grandma goodbye that I finally believed. Instead of the relief I'd expected to rush through my veins, I found myself squeezing her tight and shutting my eyes as if I could've washed this reality away if I just shut it out long enough. I was scared. Leaving Jordan meant leaving everything behind, everything familiar–the smell of za'atar baking in the morning, the toasted corn cups in school, the warmth of Teta's hands, the language that wrapped around me like a blanket. I was terrified.

IMAGE BY WINTA ASSEFA

Leaving Jordan felt less like freedom and more like losing a piece of myself. Canada was cold. Not just the weather, though the biting wind shocked me when we stepped off the plane, but the way it felt. The houses looked too perfect, too clean, as if they had been scrubbed of life. The streets were wide and empty, and I longed for the crowded alleys of Amman, filled with the hum of voices and the clatter of carts.

At school, the coldness persisted. Recess was the worst. I sat alone on a bench, gripping my dictionary like a lifeline. The other kids played tag, their laughter rising and falling like waves. I watched from a distance, feeling like an island they would never reach.

One day, a group of girls approached me. "What's that?" one of them asked, pointing to my dictionary. I'd been in school a few months long enough to make out her words, but her tone was sharp, and I could feel the sting of judgment before she even said another word.

I thought about my answer before I spoke. "A dictionary," I replied, my accent thick, and each syllable was a struggle.

The girls giggled. "Can you even read it?" another asked. Heat rushed to my face. I wanted to snap back, to defend myself, but the words wouldn't come. Instead, I clutched the dictionary tighter and looked away.

Later in class, I found my seat taken. A girl with brown hair and a smug smile leaned back. "Looks like you're standing today, butler," she sneered, her words dripping with mockery. The table group giggled. One guy eyed me guiltily but averted his gaze when I met him with my fiery ones.

I felt something crack inside me, but still, I stayed silent.

IMAGE BY WINTA ASSEFA

By my second month, I found solace in writing. At first, I struggled to fill even a single page in Mr. Brown’s blank journal, but soon the words began to flow—in Arabic and English.

Writing became my refuge. I wrote about the brown-haired girl, the other girls at school, the ache of missing home, and the questions I couldn't answer about my identity. When I said I was Syrian, people’s faces softened. “That must have been so hard,” they’d say, voices tinged with pity.

But when I mentioned Palestine, their smiles faltered. “Palestine?” they’d repeat, as if the word itself was controversial. The shift was subtle but unmistakable, as though being Palestinian was something to hide. So, I tried to push that part of myself away.

Who was I? Syrian? Palestinian? Canadian? None of the labels fit.

The journal became my confidant, a place where I could be honest in a way I didn't know how to be with anyone else.

~ ~ ~

A couple of months passed, and the bullying didn't stop. My homework went missing. My bag was rifled through. And still, I kept my head down, my anger simmering just below the surface.

Then, one afternoon, I reached my breaking point. Mr. Brown had introduced poem writing, and though I was excused from presenting, I worked hard, painstakingly translating my words with a dictionary. When I returned from lunch, the paper was gone.

I saw her—the girl with brown hair. She was holding my paper and my words, waving them like a trophy for her friends to see.

"Hey!" I yelled. The word burst out of me like a dam breaking. The room went silent, all eyes on me. I marched toward her, fists clenched, my body trembling with fury and fear. "Shoo mishkiltik?" I demanded in Arabic. The words spilled out before I could stop them. "Ana sho emiltilik?"

She froze, startled by the unfamiliar words. Her friends stared wide-eyed. For the first time, she looked unsure of herself. "What does that mean?" she asked, trying to laugh, but her voice faltered.

I curled an eyebrow, amused by her crack in composure. "Mish dakhalik."

I turned and walked away, heart pounding so loud I prayed no one else could hear it. I hadn’t won the war, but for the first time, I had won this battle.

~ ~ ~

That night, I rewrote my poem in my journal without my dictionary. I let the words flow–English when I could, Arabic when I couldn't, and scribbles or sketches when no language sufficed.

By the time I finished, I scanned the page, a small smile tugging at my lips. I knew what I had to do next.

Mr. Brown looked surprised–and pleased–when I offered to present. But now, standing in front of the class, I wondered if this was a mistake. I steadied myself, channeling my mother’s strength and the steadying ghost of Teta’s touch.

The same girls who had taunted me sat in the front row, their faces still smug with judgment. But today, it didn’t matter. I was ready.

The room quieted, waiting. I gripped my notebook, took a deep breath, and spoke.

"For so long, I tried to shrink,

To ankamish, fold into corners,

To silence the weight of my voice.

But my abjadiyah spills like ink,

My dhikrayat whisper in the spaces

Where silence is louder than words."

My voice grew stronger with each line. The girls’ smiles faltered as they exchanged glances. This wasn’t a rhyming poem; it was a declaration.

"I carried my homes like a secret:

The streets of Amman humming like prayer,

The scent of za'atar at dawn,

The warmth of Teta's hands—

Soft, calloused, timeless.

How do I fit these fragments into one name?

"I am Syrian, born of mountains and olive trees.

I am Palestinian, rooted deeper than time.

I am Canadian, learning to bloom in the cold.

And through it all, I am a writer.

Still, some parts of me will never fully translate,

But that's what makes me whole—

Untranslatable… and free."

Glossary

Abjadiyah – Alphabet.

Ankamish – Shrinking, folding into oneself.

Dhikrayat – Memories.

Ana sho emiltilik? – What did I ever do to you?

Mish dakhalik. – It's none of your business.

Shoo mishkiltik? – What's your problem?

Teta - Grandma.

📣 What Did You Think?

Your reaction helps us choose the top story of the month and gives the writer some well-deserved love.

Tap a reaction below to tell us how the story made you feel:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Hi! My name is Lamar Kassab, a 15-year-old Grade 10 student at Chinguacousy Secondary School. I’m a proud Muslim and Arab with Palestinian and Syrian roots, the middle child in a tight-knit family, and a cat mom to five.

I’m passionate about language and storytelling, though I’ll always prefer conversations with animals over people. As president of my school’s Muslim Student Association and SAC equity rep, I advocate for social justice and perform spoken word poetry, including Blink and Scroll, at events like PDSB’s spoken word festival.

I unwind with tea, candles, jazz, and my cats. I love modest fashion, reading, and spending time with close friends. Those who know me say I’m loud and fearless on stage but comically shy about asking for a second straw at a café.

I’ve been recognized for academic achievements and awarded for inclusivity and leadership. I hope to become a lawyer and use my voice to make meaningful change.